Athens Centre II

May 17, 2023

Kaisariani

May 17, 2023Lavrio

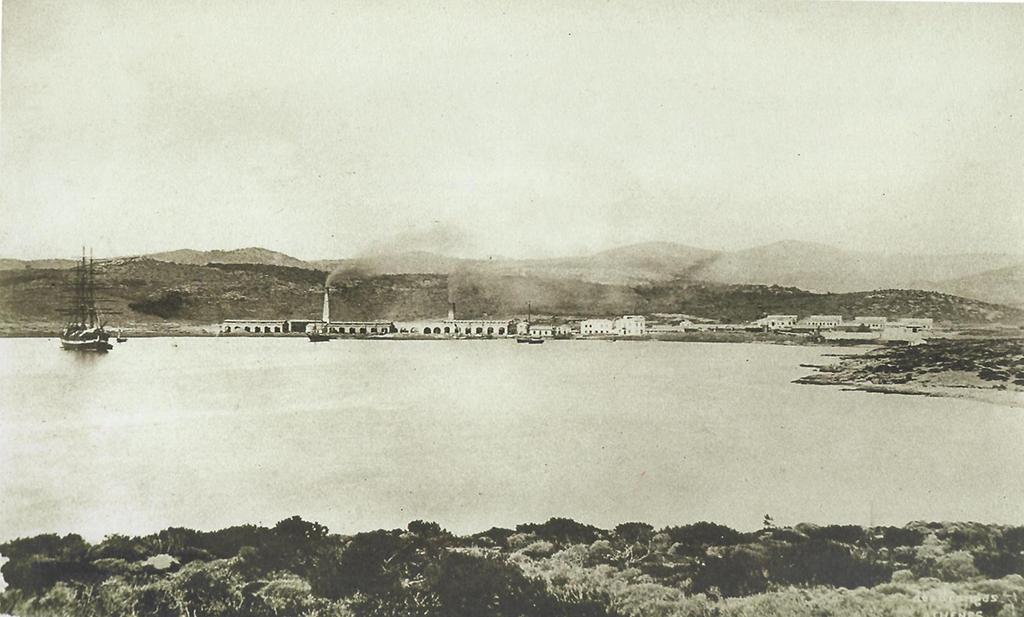

The history of Lavrio begins from antiquity and stretches to the modern and contemporary age, entangled with the mines that defined the port’s economic and social development. It is a place with significant and dense history, as attested by the mounds of ancient slag and the beach of Thorikos, with its brick kilns and nearby ancient theatre, the “crown jewel of Lavreotiki”, built with an elliptical shape and a rectangular orchestra, and largely regarded as the oldest surviving theatre in the Helladic region. Modernity, and the modern age in general, came relatively early to this place. The city was developed on a premise of industrial forward momentum, and its evolution was marked with periods of progress, as well as periods of crises, scandals, strikes, and worklessness. During the years from 1922 to 1930, it accommodated refugees from Asia Minor, Pontus, and Constantinople.

The great tragic poet Aeschylus praised the region of Lavreotiki as “argyrou pigi” (fountain of silver) and “thisavros cthonos” (treasure in the soil) for the valuable resources it provided for the defense of Athens during the classical times (5th century B.C.) – moreover, Lavreotiki also represented the “underpinnings of civilization”. Centuries later, in an unseen yet factual way, the ancient traditions of ore excavations and metallurgy, combined with the remains of mining, assisted to the revamping of the land, which had in the meantime been deserted, into a powerful hub of mining and metalworking from 1870 onwards.

The first refugees from Asia Minor arrived sporadically a short time after the devastation of Smyrna. They were mentally and physically exhausted. The numbers of Asia Minor Greeks arriving in Lavrio rose after the autumn of 1922. It has been calculated that approximately 3,000 people had come to Lavrio until the end of 1923. For the most part, they were from the lower social classes, and they originated from at least 46 different Asia Minor townships.

Industrial buildings, storage houses, loading bridges, mineshafts, electrical lighting, a somewhat urban population, a backdrop of hills, and poor neighborhoods of a working-class city and a bustling port with a long and continuing history: these were the constituent parts of the city that would welcome the refugees, integrate them, and progress and change with them.

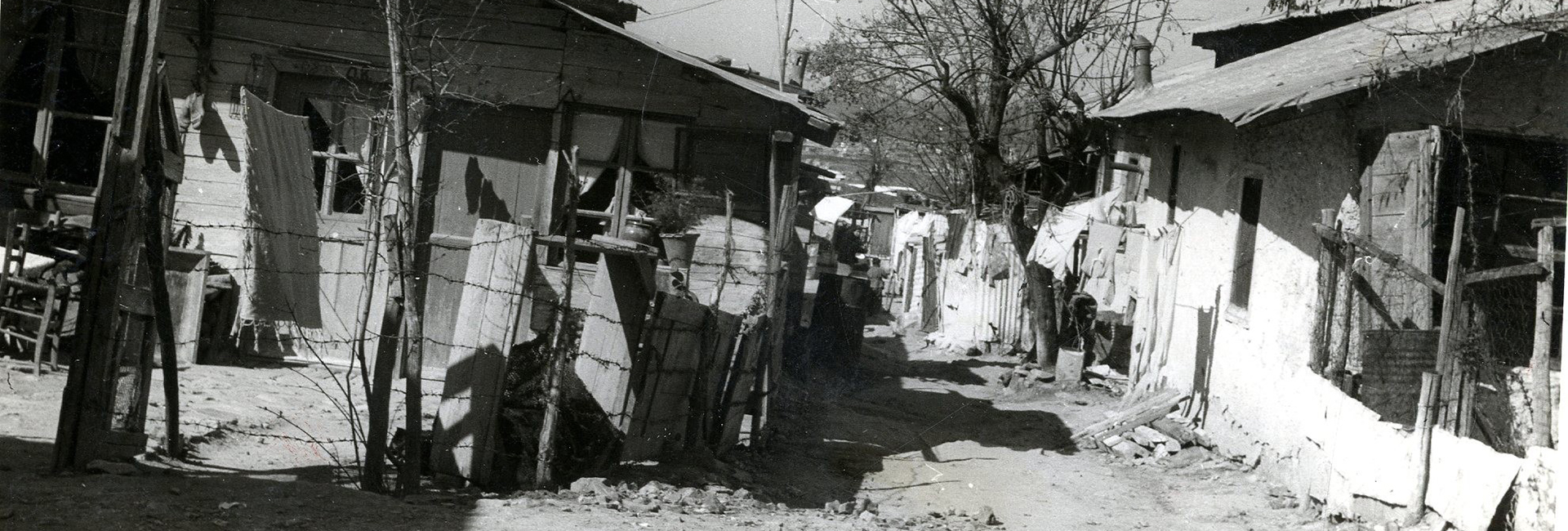

As elsewhere, initial housing will be problematic and makeshift. The Asia Minor Greeks will be accommodated in tents temporarily set up on the beach, or in outbuildings and storage houses provided by the Hellenic Mining Company of Lavrio.

Lavrio is a port, which therefore makes it a place of transition for the newly arrived refugees. Many of them will be directed to settle in other urban or rural areas around the country. The majority, however, will stay in Lavrio and breathe new life into the working-class city.

Those arriving in 1922 will prove to be comparatively more fortunate.

In early 1923, the outbreak of epidemic diseases brought the enforcement of a quarantine. The uninhabited island of Makronisos, visible from the coast of Lavrio, served as site for the establishment of the third quarantine station in the whole of Greece, the other two having been assembled at Piraeus and Thessaloniki. The very first experience of many refugees will be their quartering under deplorable conditions.

It has been calculated that a total 12,000 refugees endured the quarantine station of Makronisos.

As the wave of refugees becomes more massive, the dwelling sites are spread out. Houses in Nychtochori and buildings of the Lavrio Hellenic Mining Company were requisitioned and shacks were put up on the hill behind the church of Agios Andreas, eventually evolving into the namesake township, although its development had already been put into effect during the period from 1927 to 1928. A few of these modest refugee houses still survive to this day, wedged between tall apartment buildings.

Most Asia Minor Greeks – men, women, and even children – were integrated into the workforce of the Mining Company, in different positions and stages of the ore mining process. The working conditions were extremely harsh, and the wages were low. As a consequence, they joined the struggle for better working conditions and took part in the large strikes, before ultimately investing in the vision of Eleftherios Venizelos.

Commerce was the one field in which the refugees excelled through their experience, boldness, and inventiveness. Those few wealthiest among them, who laid the foundations for the “commercial Lavrio”, opened their shops in the heart of the town and near the old market. The latter is also the area where the renowned café chantants of Lavrio were established and frequented by musicians from Smyrna and other places, creating songs out of their memories and dreams.

The refugees put down roots in Lavrio. Their traces are visible in the history of the town, on the imposing industrial facilities which nowadays form part of the Lavrion Technological and Cultural Park (open to visitors), as well as on the heaps of ancient slag, on the low-built derelict houses, and in the din of the modern port, where histories of old continue to be written