The Refugees and the Press

At a time when the only means of communication were the printed press and the radio, the newspapers used to collaborate with many reporters and photographers who investigated each event. They also offered space to chronographers and pamphleteers who expressed their opinions on daily issues. Finally, the classified rubrics offer space to quests for services, jobs and products..

The newspapers of Attica devoted large part of their articles to the arrival of refugees, but the issue did not actually monopolize their editions. During the first weeks after the start of refugee influx, i.e. at least until mid-October 1922, the front pages focus rather on the collapse of the military front in Asia Minor, the political events and the misery of the captives than on the refugees themselves, to whom are dedicated smaller rubrics.

The Press of Athens and Piraeus

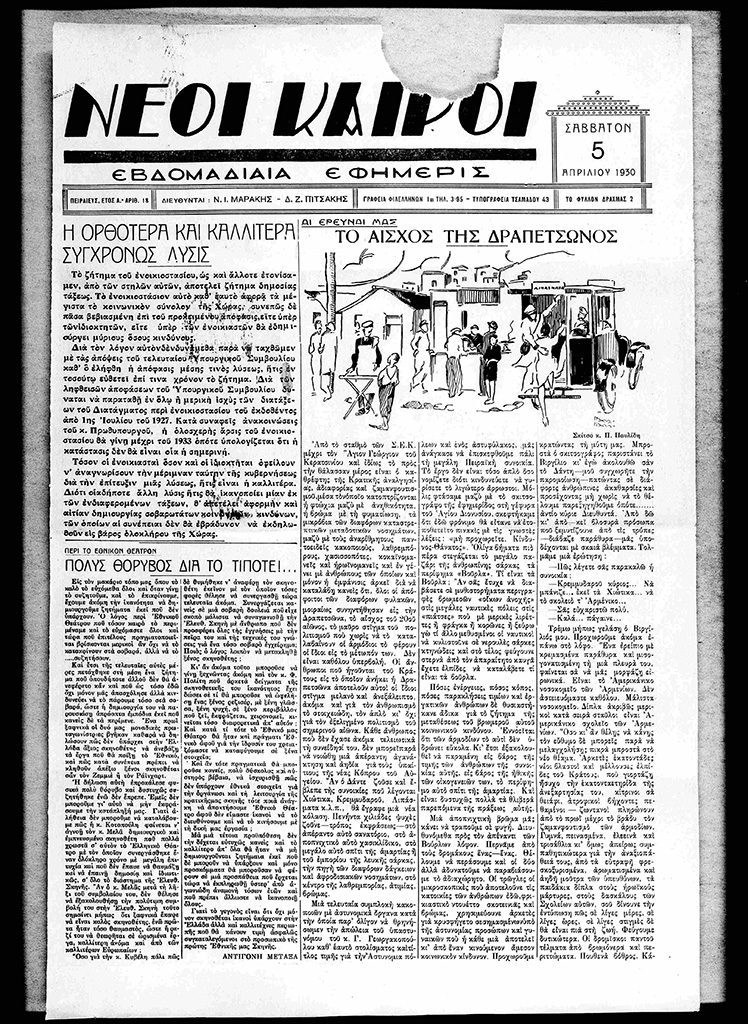

Πρωτοσέλιδο της εφημερίδας Νέοι Καιροί (5 Απριλίου 1930), με άρθρο που διεκτραγωδεί την κατάσταση των προσφυγικών συνοικισμών της Δραπετσώνας.

From mid-September 1922 onwards the big newspapers of Piraeus and Athens dedicate space to the refugees. However, it is evident that the journalists are hesitating between humanitarian feelings and the need to match the feelings of their readers. The “progressive” newspapers, particularly those supporting Venizelos, are more affectionate. Pity for the tragedy of the newcomers is prevalent. On the other hand, more conservative newspapers appear more sceptical, showcasing the dangers that refugees may constitute for the locals, such as the diseases they bring, the petty criminality and the requisitioning of houses and schools.

In Piraeus, which receives the main bulk of refugees arriving to Attica by boat, the “Chronographer” presents in short rubrics the daily picture of the port with men chasing young refugee girls and the thefts by little refugee children. On the other hand, it also advertises job positions offered to refugees by businessmen of Piraeus and keeps its public informed on the requisitioned schools. In the course of 1923 the newspaper will also stress the importance of carpet weaving as a means for the restitution of the refugees and the reinforcement of Greek exports..

The newspapers of Athens are also divided in two fractions. Acropolis, a royalist newspaper, enhances the problems caused by the refugees as well as the hostility with which part of the Athenian population faces the refugees. Along the same line, “Proini” and “Esperini”, edited by G. Giannaros, remain silent on the refugee issues and try to propagandize on behalf of the king. Exactly on the opposite side are the newspapers supporting the king’s rival, Eleftherios Venizelos. “Democracy” for example stresses the misfortunes of the refugees, the lack of sympathy by the locals and the positive things that refugees bring with them, leading to the transformation of the Greek economy and society. “Empros” by Kalapothakis, which supported steadily the revolutionary government of Plastiras and Gonatas (l. 9583, 3.7.1923) and the restitution of the refugees, becomes a tribune for the publication of the efforts to found refugee settlements. On the other hand, “Ethnos”, slightly more conservative, confines itself in news related to the arrival and transportation of refugees, the public facilities (e.g. baths) and the refugees’ quest for jobs, without lengthy comments. From 1923 onwards, the journalists stress also the efforts of the state as well as of the humanitarian organizations, the American ones in particular. For example, “Patris”, edited by Sp. Simos, exalts the role of the Union of American Women and their hospital in Kokkinia (August 17th, 1923), whereas “Democracy” (April 19th, 1924) advertises the exhibition of handcrafts made by female refugees in the Old Palace. This exhibition was the result of systematic efforts of the Christian Union of Young Ladies, of humanitarian organizations as well as of the refugees themselves to care for the professional formation of women in weaving, sewing, embroidery and knitting.

Το Σεπτέμβριο του 1923 ολοκληρώθηκε η έρευνα του Νάνσεν για την αποκατάσταση των προσφύγων, την οποία αποδέχθηκε η Κοινωνία των Εθνών. Ένα μήνα αργότερα ιδρύθηκε η Επιτροπή Αποκατάστασης των Προσφύγων, η οποία θα έπαιρνε διεθνές δάνειο για την προσπάθεια εγκατάστασης των προσφύγων σε περιοχές ανάλογες με αυτές που είχαν εγκαταλείψει. Η Επιτροπή θα αναλάβει το έργο της το 1924, μετά την υπογραφή της Συνθήκης της Λωζάννης, με την οποία θεσμοθετήθηκε η ανταλλαγή των πληθυσμών βάζοντας τέλος στις όποιες ελπίδες για επιστροφή των προσφύγων στις εστίες τους.

Ο φωτογράφος Π. Πουλίδης αποτύπωσε με τον φακό του το δράμα των προσφύγων από τις πρώτες μέρες της άφιξής τους στο λιμάνι του Πειραιά. Χαρακτηριστικές φωτογραφίες, όπως δημοσιεύτηκαν στην εφημερίδα «Πατρίς

Refugees’ Press

Many of the refugees, coming from urban centres with a long tradition in printing and journalism, managed to create their own newspapers, in order to claim their rights and to support the refugee relief and identity. The famous -and long-lived- “Amaltheia” of Smyrna is published in Athens from 1923 onwards. “Pamprosfygiki” is founded by G. Violakis in 1925 as a “Daily Tool for the promotion of Refugee and Liberation Interests”. Finally, the “Refugee World” is founded in 1927 by G. Sinanidis, in order to function as an independent channel for the information of refugees. An important publication is also the “Refugee Diary”, published once a year and containing a variety of refugee-related topics, from literary texts, settlements and buildings that host refugees, biographies of personalities originating from Asia Minor etc.

Sources

Δρούλια, Λ, Κουτσοπανάγου Γ. (επιμ.), Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Ελληνικού Τύπου, Αθήνα: ΕΙΕ, 2008

Καμηλάκη, Μ. (επιμ.), Το 1922 στον Τύπο. Από τη Συλλογή Ημερήσιου και Περιοδικού Τύπου της Βιβλιοθήκης της Βουλής, Κατάλογος Έκθεσης 2022.

Καραπάνου, Α. (επιμ.), Η αττική γη υποδέχεται τους πρόσφυγες του 1922, Αθήνα: Ίδρυμα της Βουλής των Ελλήνων, 2006

Μάγερ, Κ., Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Τύπου, 1901-1959, Αθήνα

Τζεδόπουλος, Γ., Πέρα από την Καταστροφή: Μικρασιάτες Πρόσφυγες στην Ελλάδα του Μεσοπολέμου, Αθήνα: Ίδρυμα Μείζονος Ελληνισμού 2003