Athens Centre I

May 23, 2023

Nikaia

September 26, 2023Drapetsona

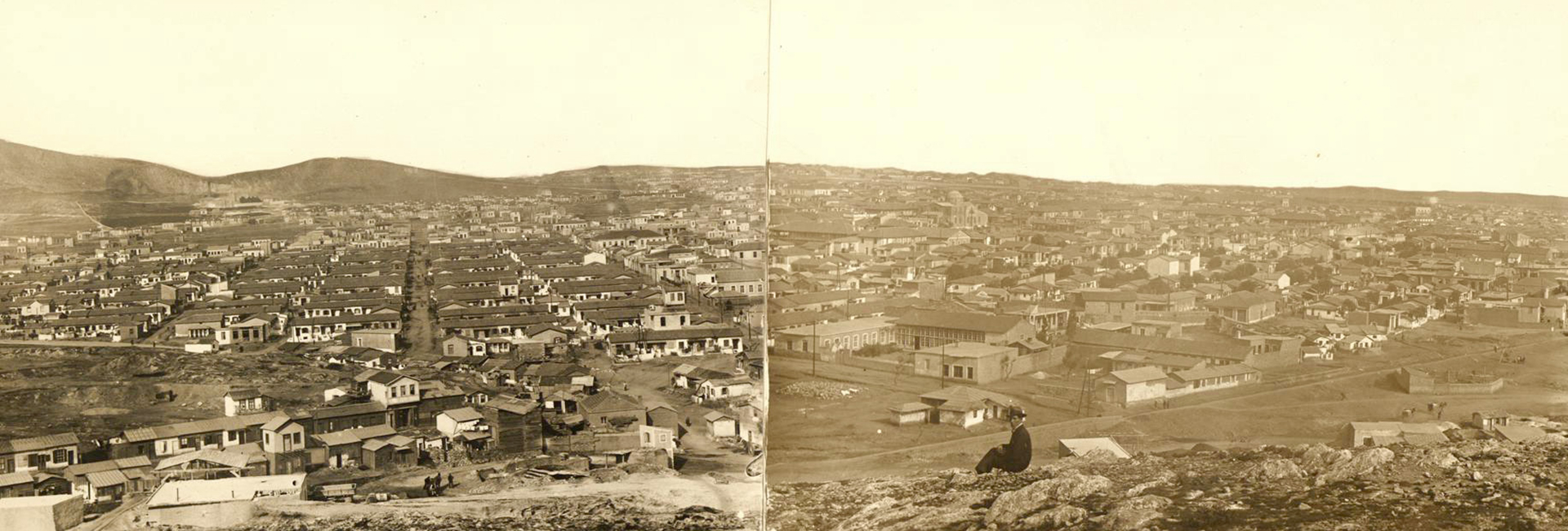

Drapetsona, which would eventually evolve into one of the largest and most emblematic refugee settlements in Attica, was a district with few inhabitants and rudimentary infrastructure up until 1922. It was predominantly an industrial area by the port of Piraeus, with important complexes along the Eetionian Coast, such as those of the Greek Anonymous Company of Chemical Products and Fertilizers (known as Lipasmata, mean. “Fertilizers”) and Heracles Cement Corporation (known as Tsimenda, mean. “Cement”). Such factories were a pole of attraction for workers. Also, since 1876, a municipal complex of brothels was in operation at Vourla, which led to the formation of its own microcosm at the district. The only neighbourhoods with an organized structure were the settlement around Hagios Dionysios and the “Oikimata”, the organized settlement of the Company of Chemical Products and Fertilizers. The latter settlement consisted of housing blocks which were actually above average for the standards of that time. The railway station began operating in 1904, and a few years later the two bridges were built, one pedestrian and one vehicular, connecting Piraeus to Drapetsona. Only two main roads were paved: Sfageia Street, later known as Kanellopoulou (and today as Ethnikis Antistaseos), which connected the station with the are of the Lipasmata, crossing the district of Vourla; and Anastaseos Street, which led to the then new cemetery at Anastasis, in Keratsini, passing through the area of the military warehouse known as “Pyritidapothiki”). Such was the outlook of the area in 1922. The settlement of the Asia Minor refugees would change its character profoundly.

The settlement of refugees in Drapetsona was not the result of planning by the authorities. The makeshift camps at the railway station and in Hagios Dionysios gave way to makeshift shacks, as refugees who did not leave for other cities or could not find a place in the housing programmes in other areas, took jobs in factories in the area and remained close to their place of work. Along with working in the factories, those who knew a craft made their shelters into makeshift workshops. Despite the population boom, organized state intervention remained minimal. Drapetsona was not included in the plans of the Refugee Settlement Committee (RSC), and its districts were spread out haphazardly, creating a large and labyrinthine slum, with no provisions for lighting, running water supply, or sewage.

Drapetsona became essentially a refugee-workers' town, enveloping the Vourla district and its microcosm. In various parts within the neighbourhoods of the area, clandestine tequettes (opium dens) were formed, where the subculture of the rebetiko flourished. In such places, the urban popular music of Piraeus met with musical elements and traditions from the Asia Minor and Constantinople, to develop into the more distinctive genre which is today known as rebetiko music. From the Karaiskaki Square to the tequettes and cafes of Kremmydarou, Chiotika and Anastasis, Piraeus would be inextricably linked with legendary figures (rebetes) of this now famous genre of urban popular songs, such as Giorgos Batis, Markos Vamvakaris, Anestos Delias, Giorgos Kavouras and many others. It is no coincidence that the bridge over the train tracks at Hagios Dionysios, a symbolic boundary to Drapetsona, was called the “bridge of the rebetis”.

Vourla and their marginalised ecosystem, together with the lack of basic sanitary and urban infrastructure, determined the way in which Drapetsona appeared in the press for over a decade. Publications about the “hell of Drapetsona”, presumably an impenetrable den of crime, painted a grim picture. At the same time, the associations formed by refugees and residents were making enormous efforts to deal with the problems of the settlements and to support the lives of their inhabitants. They constantly called for the removal of the Vourla and the dangerous military warehouse of Pyritidapothiki. In 1929, they managed to coordinate their efforts through the Drapetsona Executive Committee, and the following year they secured the support of Eleftherios Venizelos to promote their demands. Their activity led to a demand for administrative autonomy from Piraeus, which would eventually lead Drapetsona and Keratsini to become separate municipalities, as is still the case today.