Egaleo

May 17, 2023

Drapetsona

May 23, 2023Athens Center A'

As the historian G. T. Mavrogordatos remarked, “The rehabilitation and assimilation of refugees from the Asia Minor Catastrophe was and still is the greatest peacetime achievement of the modern Greek State”. It undoubtedly had a deep impact on all aspects of life in the Greek territory, both in the cities and at the countryside. The effort of the Greek State to rehabilitate the often disparate populations, who arrived in waves, cannot be easily and unequivocally evaluated positively or negatively. As it has already been said, the situation was unprecedented and complicated at all levels”.

The largest part of the population flows settled in the cities. According to the 1920 census, the population of Athens was 290,000; eight years later, it had reached 460,000. The capital city was literally flooded with impoverished Greeks of Asia Minor, the majority of whom were elderly, women, and children, who sought temporary shelter and some food to ensure their survival until the next day.

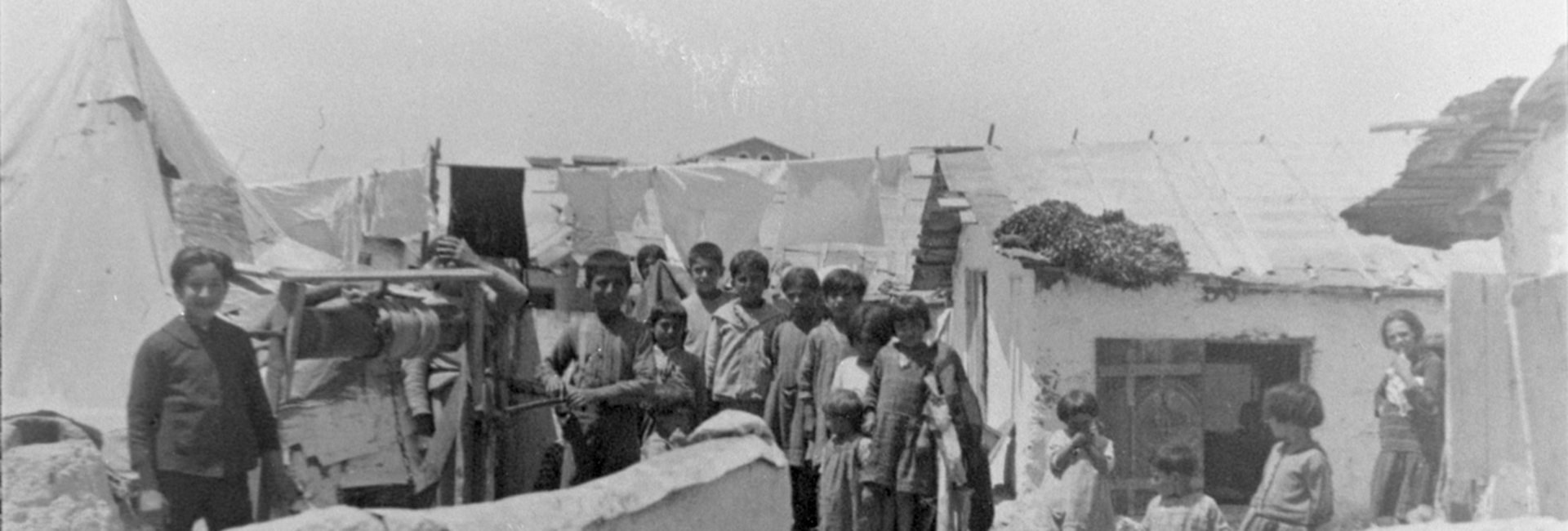

Tents and makeshift dwellings were put up in open free spaces. Public buildings, theatres, cinemas, gambling houses, warehouses, offices, hospital, and, naturally, houses, were requisitioned by the State. The Municipal Theatre, Zappeion Megaron, and the Old Palace (the current Parliament Building of Greece), accommodated families, orphans, and services. Streets, squares, riverbeds, parks, as well as open archaeological sites, became reservations and places of provision of rudimentary healthcare assistance.

The living conditions were literally atrocious, while health and hygiene conditions were plainly and simply hazardous. The density of the population during the 1922-1923 period was very high, and the competent public services were inadequate. There were outbreaks of epidemic diseases, along with recorded cases of typhus, measles, scarlet fever, meningitis, chicken pox, dysentery, and cholera.

The state administrative services providing government assistance and rehabilitation were completely unprepared to handle the arrival of such large refugee waves. Charities, as well as international organizations, stepped in to lend their support. Refugee camps were gradually assembled both in Athens and on its outskirts. As the winter of 1922 set in, many children and sick refugees began to die from hunger and cold. Mortality rates increased. The image of the begging refugee in tattered clothes became commonplace – first in real life, and afterwards in art. The refugees felt abandoned and “foreign”, while the native-born Greeks felt threatened. The Hellenicity of refugees was often doubted. The conservative societies of urban and rural native-born Greeks became acquainted with new values and habits, many of which they could not easily accept. The difference in lifestyle and language increased reluctance, if not outright hostility, and gave rise to the locals’ sometimes clearly racist treatment of the newly arrived people.

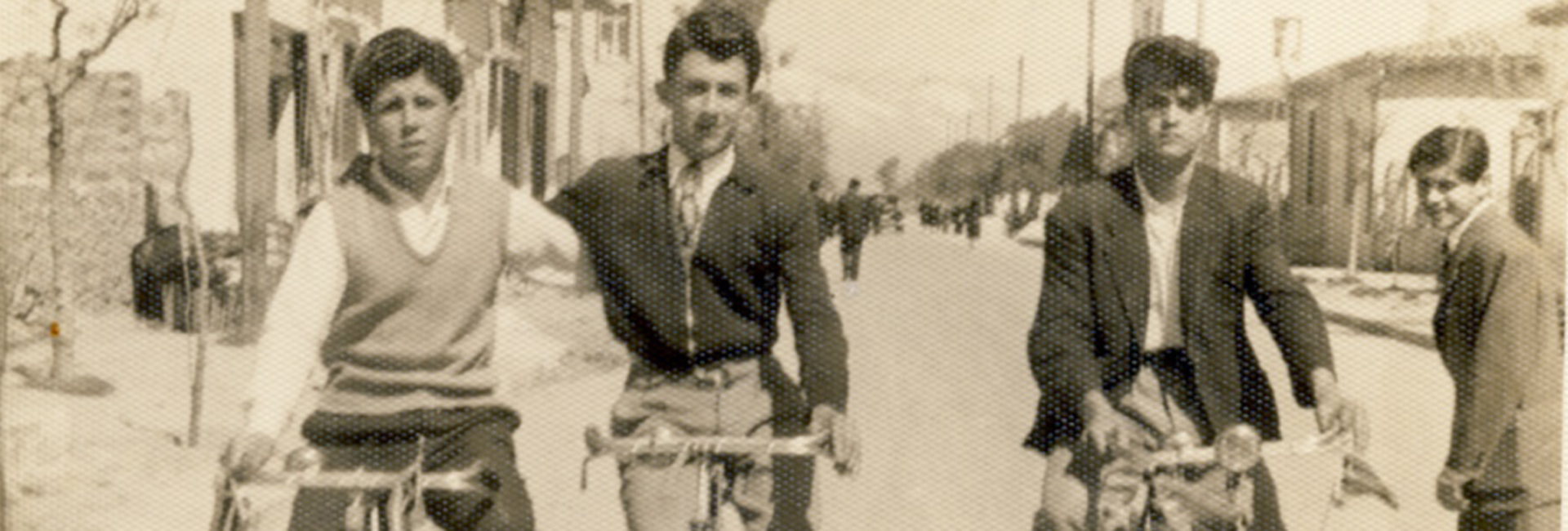

Despite the difficulties, the refugees fiercely forged an identity of their own, that of the “displaced”. They brought with them symbols of their homeland, along with festivals, songs, and habits. They stood in solidarity with each other, they were stubborn, and, in the end, highly creative. It is a fact that, as the historian Kostas Kostis wrote, “After the arrival of the large refugee waves, the division between natives and refugees became a major political and social feature of Interwar Greece”.

Nevertheless, since the path of return has been permanently closed, coexistence is a requirement that will become a necessity; as the years go by, this osmosis will give rise to new perception of collectivity.